Your cart is currently empty!

A journey through time: The Sound Revolution at the Constitution Hall in 1933

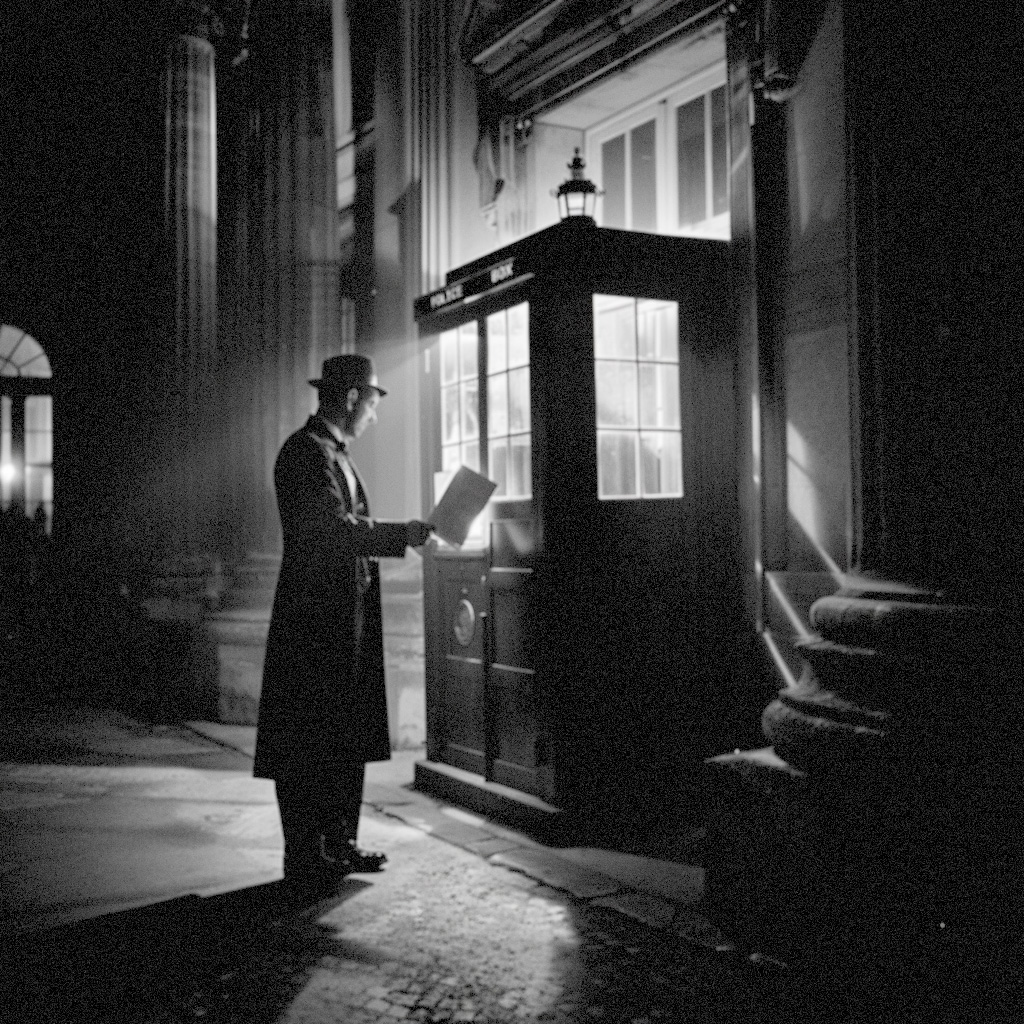

Let’s begin with an exercise in fantasy: Imagine you accept the proposal to embark on a time-travel journey aboard the Tardis, which transports you directly to the bustling 1930s. Now, visualize yourself holding an ornate and elegant formal invitation to attend one of the first public demonstrations of a revolutionary entertainment system, designed to fill auditoriums with sounds never heard before. You are now in front of Constitution Hall in Washington D.C. on the night of April 27, 1933.

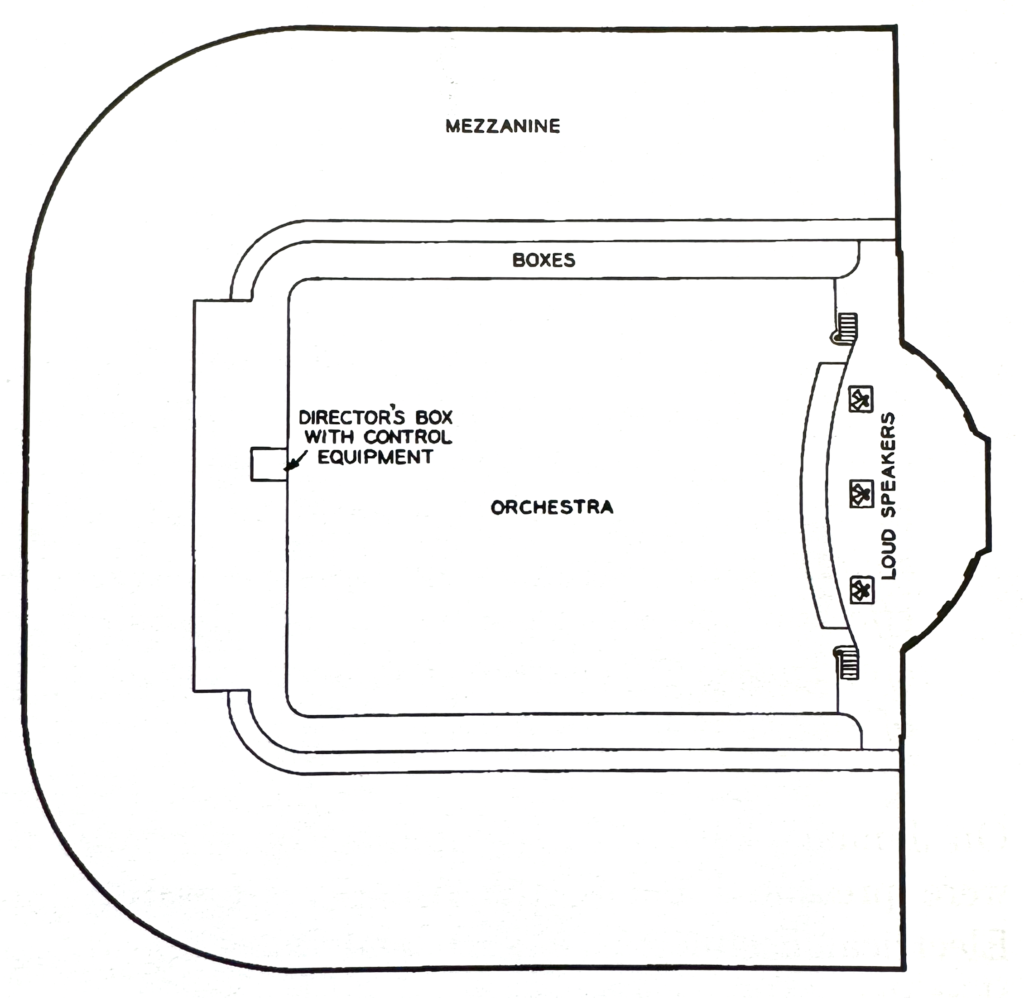

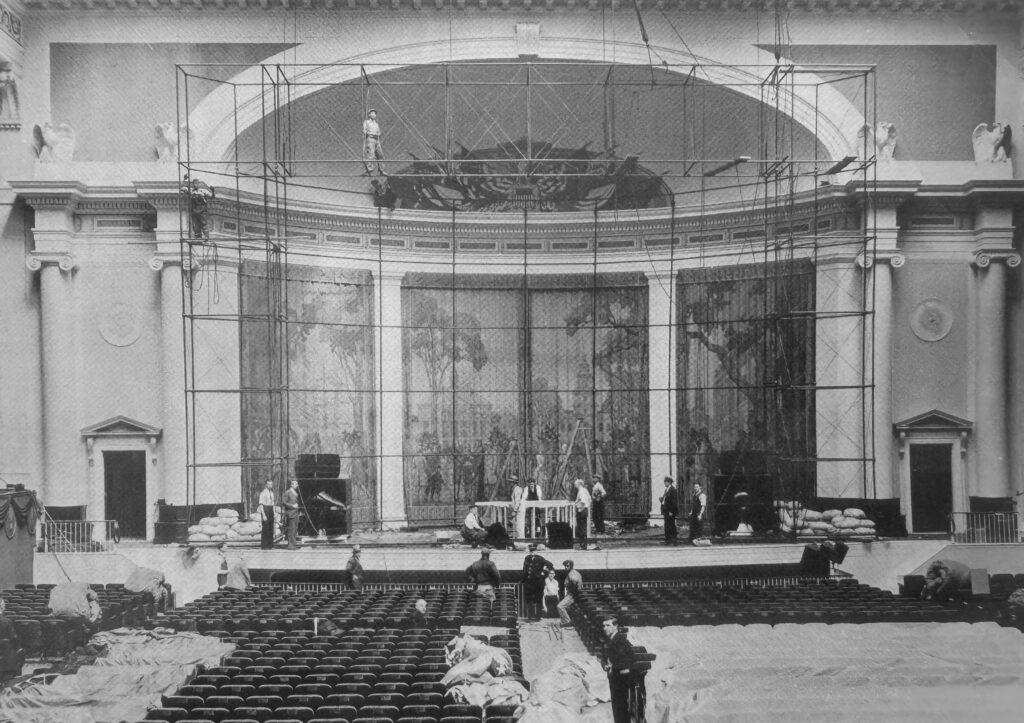

As you enter the imposing auditorium, you head to your seat in the Mezzanine. As you walk, the murmurs of the crowd cease, the lights dim to the point where only the silhouettes around you are perceptible, and the expectant silence is broken by an overwhelming sound. An intense spotlight shows a diminutive Stokowski manipulating the controls from a booth at the back of the hall. Over 300 km away, in a rehearsal room in Philadelphia, co-conductor Alexander Smallens directs a small orchestra of musicians. In the Washington venue, the sound is reproduced “live” by a single-ended vacuum tube amplifier with a staggering 4 Watts of power across 3 channels connected to a set of 3 large horn speakers strategically placed on the stage, a system recently developed in the laboratories of Western Electric. “The climaxes were overwhelming for the audience…” described a New York Times reporter present, unable to contain his enthusiasm.

Dr. Stokowski, master of these invisible sounds, carefully adjusted the switches, orchestrating an auditory spectacle that made the far away orchestra sound like an army of musicians, multiplying it in power and emotion.

During the performance, the audience heard a scene transmitted from Pennsylvania to Washington. On the left side of the stage in Philadelphia, a carpenter was building a box with a hammer and saw. On the far right, another worker was making suggestions to his colleague. “The effect was so realistic that it seemed like the scene was happening on the stage in front of the audience. Not only were the sounds of sawing, hammering, and talking faithfully reproduced, but the auditory perspective allowed listeners to place each sound in its correct position and follow the actors’ movements by their steps and voices,” wrote an observer. Next, a soprano sang “Coming Through the Rye” while moving across the stage in Philadelphia. In Constitution Hall, the ghost of her voice “seemed to be wandering on the stage.” The program continued with the remote orchestra playing Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, and finally Wagner’s Götterdämmerung. ERPI provided visual accompaniment. The show culminated with an unforgettable duel between two trumpeters: one in Philadelphia and the other in the hall.

“To those present in the audience, it seemed as if there was a trumpeter on each side of the stage in front of them. At the end, when the stage was illuminated, they realized that only one of the trumpeters was present in person, everyone was left open-mouthed,” wrote Harvey Fletcher, founding president of the Acoustical Society, and leader of this project within Western Electric laboratories, in his memoirs at the end of the 20th century.

Most of the reviews were extremely positive. The New York Times wrote about the performance that night:

“The climaxes were overwhelming for the audience. Dr. Stokowski supervised the interpretation of the invisible orchestra under Mr. Smallens’ direction. The opera singer’s voice rose above the instruments. With his hand on the switches, Dr. Stokowski achieved the desired effect, so that even without audible amplification, the orchestra sounded as if it had more than the usual foundation provided by basses and tubas. The musicians present were very impressed with the show. In building the crescendos to the climaxes, it seemed as if an army of 100 men was playing…“

The system which had impressed the audience that night in 1933 had been meticulously created in the laboratories of Western Electric (a department within the giant Bell Labs conglomerate, which had grown thanks to the invention of the telephone) through continuous efforts in the previous decades, drawing on the experience of creating telephone systems and public addressing systems (or PA, a term that interestingly remained linked to professional sound systems even a century later).

Calibrating the positions of the microphones in Philadelphia and configuring the set of speakers in Washington took months. Much of the theory of auditory perspective was defined, but the execution required a lot of improvisation and trial and error. Originally, there were supposed to be nine speakers on the stage, arranged in a three-by-three matrix, creating a “wall of sound.” But Fletcher and his engineers realized that only three horizontal speakers were needed. In an interview, he recalled: “Well, we were just naïve enough to realize that on stage, people don’t jump up and down… perhaps for something like Hamlet’s ghost, it would be appropriate to have the speakers working vertically.”

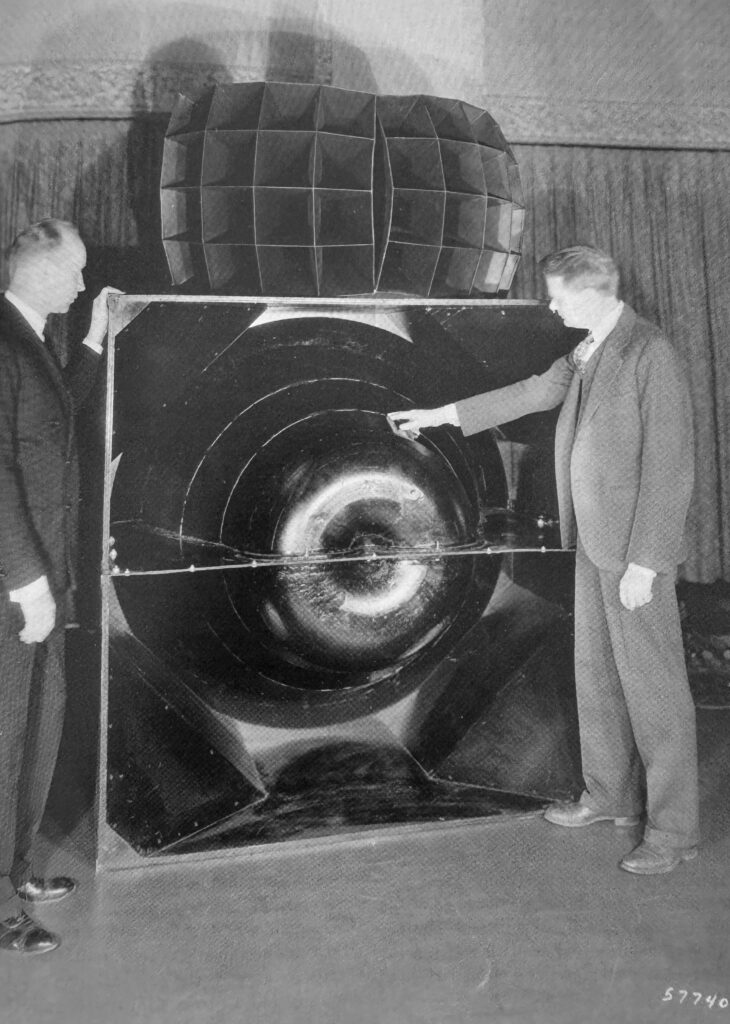

The speakers demonstrated that night were a special invention. Based on a study during the rehearsal season by engineers Wente and Thuras, the speakers were designed to have a large horn to transmit low-frequency sounds, with two high-frequency horns positioned at the top. This was inspired by Wente and Thuras’ discovery that low-frequency sounds were less spatially directed than high-frequency sounds, and thus, a natural compromise in the reproduction system could be achieved by allowing the two registers to be transmitted in different ways.

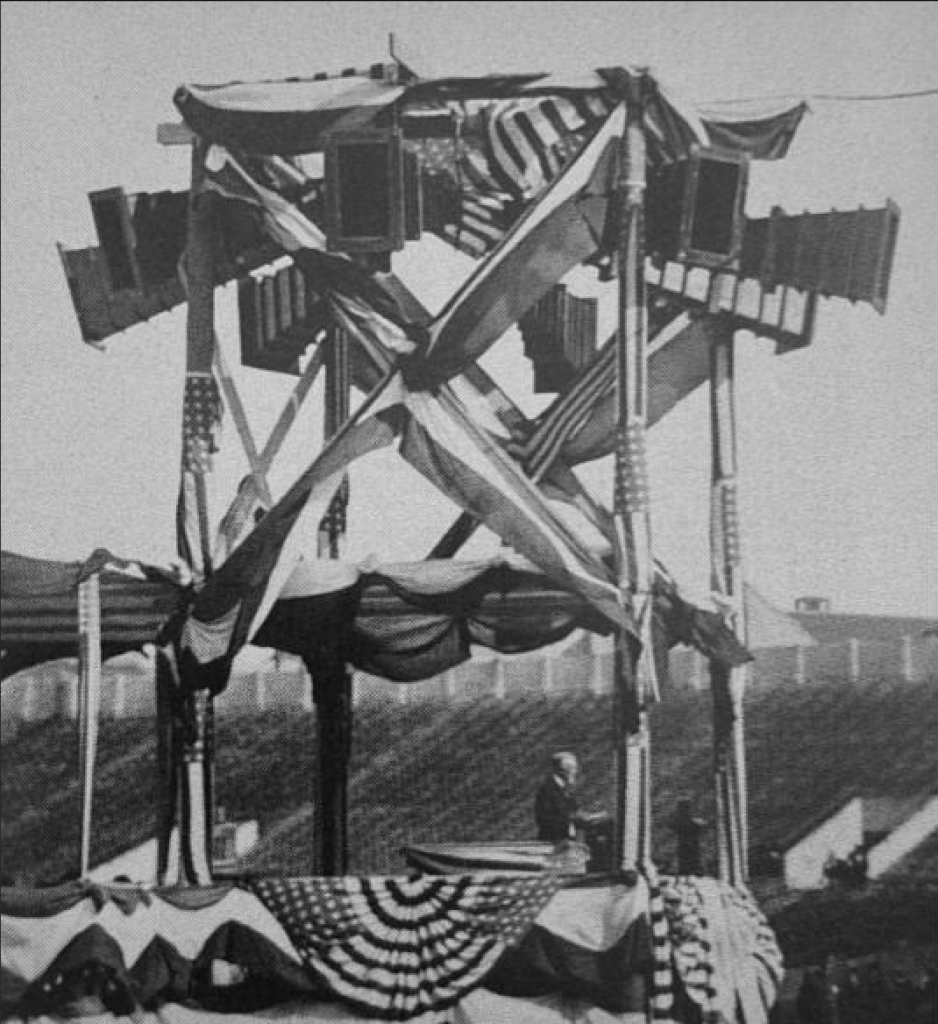

The left and right speakers consisted of two bass horns with an extension creating a mouth of 3×3.6m, offering directivity up to 50 Hz, and four multi-cellular horns for mid and high frequencies, each driven by two compression drivers. The central channel consisted of a bass horn with a mouth of 3x3m and two multi-cellular horns. In total, two and a half tons of speakers were mounted on a bridge structure above the orchestra shell. It is estimated that 25,000 people could easily hear the show from any point in the hall.

The analysis equipment used by Fletcher’s team to study the various iterations of this system was rudimentary by today’s standards, so much was developed “by ear”: analytical intelligibility tests, such as counting the number of words “understood” through reproduced sound by different people, created subjective standards for evaluating sound systems that measured parameters such as “naturalness,” “organic sound,” or “illusion capability.” This approach is now heavily criticized and confined to experimental audiophiles who reject purely objective analysis, prevalent in the contemporary consumer high-fidelity industry (interestingly, the same subjective analysis parameters are still accepted and used today in the professional audio industry to describe a system).

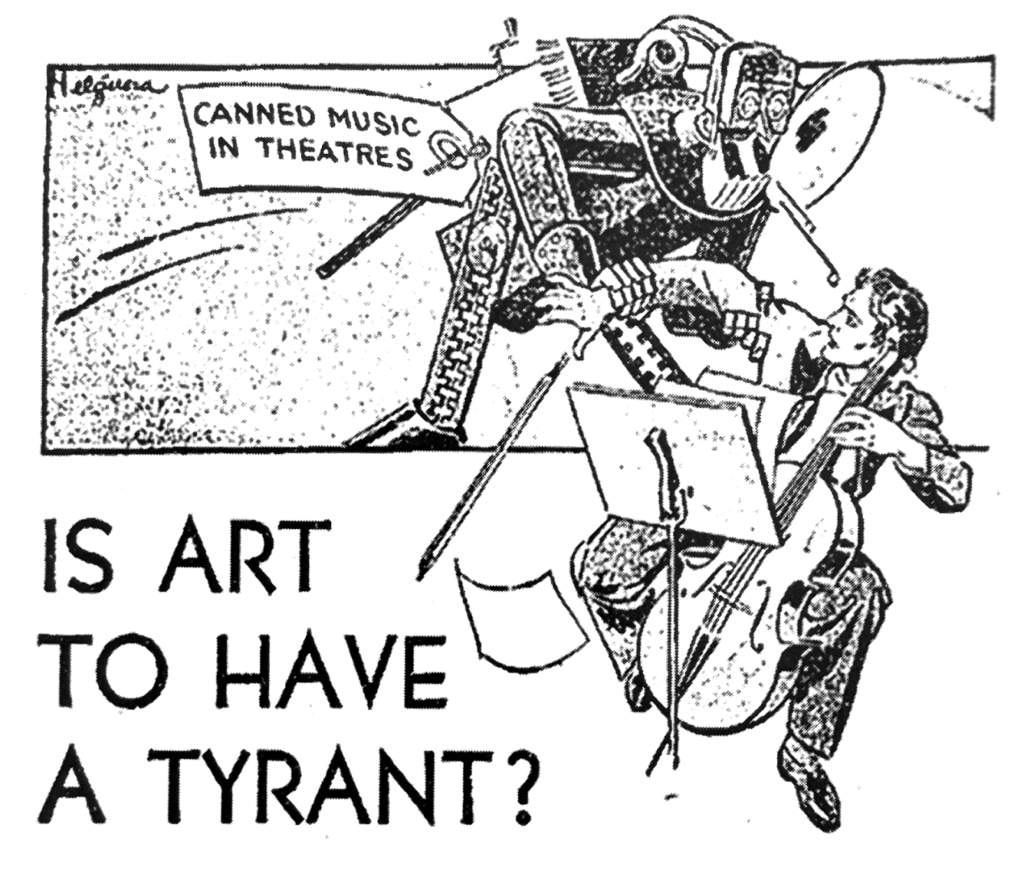

The Beginning of the Consumer Audio Industry Branch

The efforts of World War II introduced new elements into vacuum tubes. The noble triode (with three elements: cathode, control grid, and anode) was improved by adding more grids, resulting in the tetrode and pentode. This aimed to reduce the parasitic capacitance (also known as “Miller capacitance”), which limited the bandwidth that triodes could amplify, making them impractical for radiofrequency amplification. Another goal was to increase the effective power of each tube, promising the capability to drive more compact speakers. The era of consumer high-fidelity began, prioritizing convenience and miniaturization over the original purpose of naturalness and convincing illusion.

Just as a truck is naturally more efficient at moving tons of sand from one place to another than a wheelbarrow, a large speaker is more efficient at moving large amounts of air than a small one. As Paul W. Klipsch noted, “no one has yet discovered how to shrink a 32-foot wave” (approximately 10 meters or a wavelength equivalent to a frequency of 30Hz under normal propagation conditions).

Of course, there has been progress in speaker science. We now have stronger and lighter magnets, materials that can withstand higher temperatures and mechanical stress, better production methods, and designs that allow us to optimize speakers for previously impossible ranges. We can design speakers that are reasonably efficient at larger displacements than before. More powerful amplifiers make it possible to use low-efficiency speakers to some extent. We also understand more about speaker acoustics and psychoacoustics, making it possible to design speakers that are generally preferred by the public. However, these speakers are mostly designed with inherent limitations in size and the ability to fit into a normal living room.

The fact is, there is no Moore’s Law for speakers. There is no “acoustic transistor” that allows for miniaturizing speakers. Therefore, speakers are subject to constraints, like the wheelbarrow, and these constraints cannot be circumvented by new materials or design tools. We cannot miniaturize the speaker without paying a price.

Meanwhile, the professional audio industry, with deep roots in the traditions of Western Electric, remained faithful to established principles. Brands like RCA, Electro-Voice, Altec, and JBL continued to develop sound systems that honored authenticity and sound quality above all. Being inherently free from the space restrictions imposed on the consumer audio industry, they continued to perfect the original recipe, achieving acoustic transducers with greater efficiency and capable of reproducing a wider range of frequencies with increasingly less distortion. These systems are still revered today and follow the original Western Electric line, winning the best sound award every year in Munich, at the annual high-fidelity convention “High End Munich.”

The early sound systems, with horn speakers and single-ended vacuum tube amplifiers with very simple circuits, although seemingly rudimentary by modern standards, had an almost magical quality. Without the pointer of a measurement “standard” and armed with much naivety and sensitivity, those Bell Labs pioneers were free to explore the “reproduction of naturalness,” and the surviving accounts of firsthand witnesses are honestly hyperbolic for very good reasons.

It would be easy to fall into the temptation of thinking that the “primitive” audience that attended that demonstration in Washington in 1933 was so impressed because they had no point of comparison: after all, they were among the first people to experience an electrically amplified entertainment sound system. But we must not forget that this audience was used to hearing unamplified music in similar auditoriums, as this was one of the main ways to appreciate music at the time. It is hard to imagine a better-prepared audience to evaluate the result of the experience than this one.

It is also easy to associate professional sound equipment with music festivals where the main objective is to achieve a high volume capable of covering a large venue, far from the audiophile demand. I know firsthand that this is a common mistake and prejudice: anyone who has never heard a purist single-ended amplifier connected to a large horn speaker, like the great systems that left large audiences astonished in the years immediately before World War II, doesn’t know what they’re missing.